1 Envisioning a health data commons

1.1 The need for a data commons

Digital transformations call for a new understanding of the concepts of public health and universal health coverage (UHC).1 Digital technologies are changing notions of health and wellbeing and offering new tools through which public health goals can be achieved. However, this does not mean that achieving UHC in a digital world will only depend on a rapid pace of adoption of new technologies. On the contrary, given the wide scope of UHC, it becomes clear that achieving UHC in a digital world will inevitably require more than the adoption of new technologies in health and health care as a means of simply increasing efficiency or cutting costs.

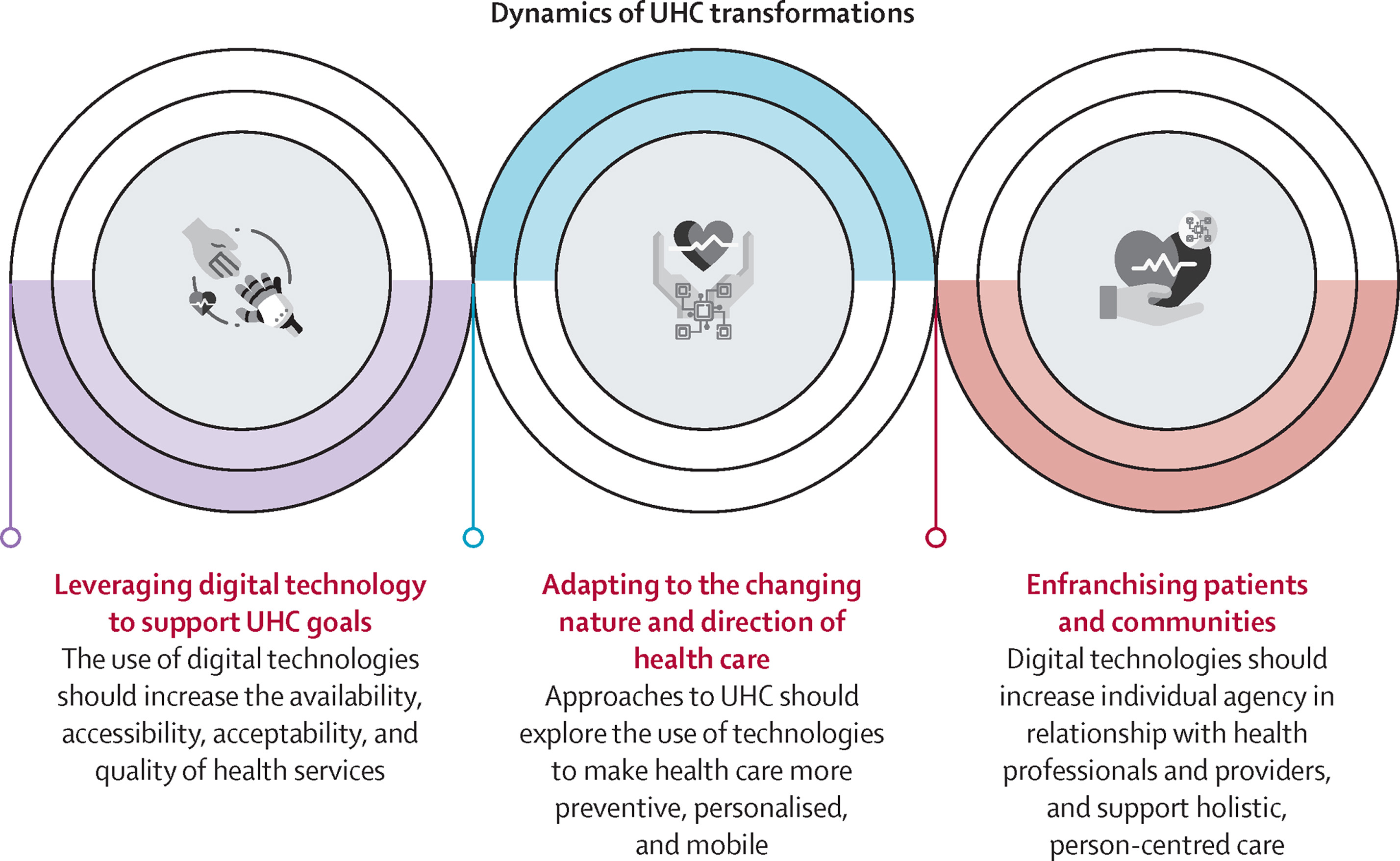

The first key question will be whether digital technologies help increase the availability, accessibility, acceptability, and quality of health services as we know them. The second (and related) question concerns the changing nature and direction of health care, and the possibility of making it more preventive, personalised, and mobile through the use of such technologies. Finally, the third question relates to the extent to which digital transformations will enfranchise patients and communities (and particularly vulnerable groups including children and young people) and evolve their relationship with health professionals and providers, thus helping shape the health system according to the needs of the patients and communities. These three dimensions of digitally transformed UHC is visualised in figure 1.1.

To illustrate these dimensions, consider the following examples for low- and middle incomce countries (LMICs).

…

Digital interventions targeting people with noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) show potential in LMIC settings.2 mHealth programs designed to support engagement in behaviors associated with diabetes, stroke, and cardiovascular disease management have resulted in improved clinical outcomes, health behaviors, and compliance with treatment, although not all published studies have shown positive effects. mHealth has also been used successfully in the remote monitoring of people with long-term conditions and in the provision of personalized medical advice based on the data received. mHealth interventions designed to promote physical activity and healthy diets for NCD prevention have shown promise in LMICs, providing a viable mechanism to improve diet and physical activity behaviors. A review of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) on the effectiveness of mHealth interventions on physical activity and diet outcomes in developing countries reported consistent findings with systematic reviews of mHealth interventions carried out in HICs.

Ongoing examples of digital interventions for NCDs include:

- add example + URL

- add example + URL

- add example + URL

…

The notion of utilising digital technologies as a means to catalyse UHC is dependent on a new approach to the collection and use of health data. The Lancet and Financial Times Commission stresses the need for applying

“… the concept of data solidarity, with the aim of simultaneously protecting individual rights, promoting the public good potential of such data, and building a culture of data justice and equity.”

Despite the long-standing adoption of broad strategies and declaration of principles to guide digital transformations, in practice, many countries still do not have effective approaches to digital health that data solidarity at the centre. Choosing who can access data and use it is in fact a central societal question we have to answer. We need to develop a sustainable information ecosystem that shifts the power balance, and control over data, back to the societies. This can be achieved through democratic management of data as a commons. Hence, we take the concept of (health) data commons as one of the foundational concepts with which we seek to align our work.3

1.2 Design blueprint for data commons

For data to be governed as the commons, we need an appropriate design of the data ecosystem. Defining the basic elements of a design blueprint for data commons is necessary for a plurality of institutions, initiatives and infrastructures to work together, or at least in parallel, on attaining shared goals. Design of data commons needs to consider three pillars, as shown in figure 1.2.

Stewarding access

Data commons deploy various forms of access to ensure on one hand that generative characteristics of data as a resource are not limited, and on the other that it is shared in a way that is sustainable, preserves rights and minimizes risks. Design decisions that concern Stewarding Access establish the rules and means for deciding who gets to access data and under what conditions. There is a tension here that needs to be resolved: between Open Access commons and stronger, permissioned forms that limit access through more refined governance. Stewardship also entails maintenance of the data and related infrastructures – as ensuring access requires large amounts of effort to collect, store and maintain quality of data.

Permission interface

Where Open Access data commons permit everyone to access and use data, other forms of commons need to be based on permissioned access. Thus, a permission interface needs to be designed. The interface may monitor, register and assess impact of requests to access data. Ensuring that the identity of an actor that is requesting ac- cess to data is transparent allows for greater accountability, also in terms of preventing harm and levying sanctions if data commons have been abused. Permissioned access is particularly relevant for creating a health data commons.

Privacy-enhancing technologies

Satisfying data protection by design (GDPR) for personal data can be achieved by conscious architecture choice. Since it is the societal objective that is important, not technological novelty in itself, greater protection of rights should be achieved with privacy enhancing technologies (PETs) such as Open Algorithms (which “move algorithm to data”), federated learning, pseudonimization, distributed vetting ledger and others. While the focus of the data governance debate is on privacy, care should be taken to preserve and enhance other rights as well.

Collective governance

Data commons are linked to the community which manages them, and in many cases generates the data as well. Any other arrangement would constitute an appropriation of the resource, and disempowerment of the people. To establish collective governance over data, there must be either an existing or a newly established entity that can become trusted institutional vehicle for data commons.

Defined community

In order to ensure democratic governance, the community that is the primary holder of rights in data needs to be defined. In this way, collective rights in data can also be better assigned and represented. Yet this is often challenging with regard to digital data, as traditional community or group formation frames do not apply. The challenge lies as much in conceptualizing the community, as in defining the right institutional level of civic life at which the collective interests should coalesce.

Trusted institution

A trusted institutional actor capable of stewarding the commons is a necessary element of data governance design. Data commons institutions are needed due to limitations of both grassroots organizing and market incentives. Institutionalizing the data commons, and thus supporting them with dedicated infrastructure, funding and capacity, renders them independent from market or state pressures.

Democratic control

For the community to have greater autonomy, it has to be directly involved in decision-making. Different forms of democratic participation or accountability can be deployed, including supervisory councils, citizen panels and assemblies, sortition and quadratic voting. Different forms of democratic control can be deployed at all levels of social life, from the local and municipal level to the governance of national datasets.

Public value

A successful data commons strategy needs to take into account not just the management and provision of data, but also the need to ensure that the gener- ated data-based products and services increase the common good. The notion of public value is useful to emphasize concrete, observable benefits produced for the society as a whole, and not just for the community that manages a data commons. By providing public value, data commons can restructure the data value cycle, change the balance of power and introduce a regenerative function to the data ecosystem. A public value perspective also pays attention to positive externalities of data commons, such as increased data literacy or experiences with civic participation.

Mission-oriented data commons

Data commons initiatives should be guided by the values upheld by the community and oriented towards societal goals. Thus, access to data is not a goal in itself, but should lead to socially beneficial uses. A mission-oriented approach ensures that data commons benefit the society in an egalitarian, inclusive manner, for example by prioritizing or incentivising data use for socially important aims.

Common wealth licensing

There is a need to build a new generation of licensing tools that allow access and use rights to be managed in as standardized way as possible. As a general principle, a license for data access and use should aim to build the shared wealth of community, by sharing the products and revenues back with the commons, and with the society – instead of just producing commercial value.

Data literacy

All commons have to remain sustainable by not only regenerating their stock, but also the capacity of the community to continue commoning. In the case of data commons, this means supporting projects of redistributive justice and reducing inequalities in the capacity to obtain value from data commons. Broadly understood data literacy includes not just individual education and training, but increases in the capacity of different actors, institutions and communities to make beneficial uses of data.

1.3 Building a data commons, one data station at a time

The aim of the Health Data Commons (HDC) project is to demonstrate a real-world implementation of such a data commons ecosystem specifically for healthcare using the framework shown in figure 1. This document focuses on the technical aspects of the design, implementation choices and learnings from various projects that have been conducted at PharmAccess Foundation since 2022. As such, the work presented here pertains to stewarding access: how can a HDC be implemented that supports a practical framework for health data sharing, incl. permission interface and support of privacy enhancing technologies. To do so, the following design principles have been adopted.

Hourglass model: build a data network, not a single solution

Over the last few years, the importance of interoperability of systems and reuse of data has become evident. One of the key challenges in establishing interoperability the dilemma of how to start: start small, and run the risk of not achieving common standards. Start large, and get bogged down in talking rather than buiding a new standard infrastructure. To tackle this challenge, we follow the concept of the “hourglass” model (figure 1.3). The hourglass model is an approach to layered system architecture where a middle layer is intentionally constricted in order to support flexibility in the implementation of layers above and below. Above the spanning layer are applications, and below the spanning layer are supports. Beck (2019) provides a formal analysis of the hourglass model which states that

a weaker layer specification has fewer possible applications but more possible supporting layers than a stronger layer specification.

We believe that the hourglass model provides a plausible road towards an ecosystem of health data as a common good, where data sharing is facilitated through a decentralized, federated network of data stations. These data stations are designed in such a way that it provides the minimal standardization to allow stewarding access all parties is the ecosystem, including healthcare facilities, government organizations, commercial companies etc. The data is not shared through centralised platforms, but is organised through local data stations. In analogy with the Internet, each data station is an independent node that acts as a webserver, interacting with other nodes to create a data sharing network.

FHIR as the de facto data standard in healthcare

Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources (FHIR) has become the de-facto standard for clinical information exchange in the healthcare sector, both for routine health data exchange4 and research settings5, and as is exemplified by the new collaboration between HL7 International (the governing body of FHIR) and WHO.6 FHIR is increasingly being used in LMICs as well: the WHO reference app for antenatal and neonatal care is built on the FHIR-based OpenSRP digital platform.7 The mHealth4Afrika project takes a comprehensive community-based approach in co-designing and validating a modular, multilingual system based on FHIR.8 Ejo Health piloted a solution Rwanda whereby community workers were provided a tablet, and demonstrated time-savings for administrative tasks and improvements in terms of safety and ease of work through digitizing the record-keeping process using the FHIR-based Aidbox platform.9

To date, the lion’s share of FHIR-related projects in LMICs focus on creating open digital health platforms, that is, achieving openness and interoperability at the level of Point of Service systems The object of openness are the software components themselves, where openness is achieved through open sourcing FHIR implementations, such as HAPI FHIR10 or through APIs as specified by the FHIR standard. For example, the SMART on FHIR standard provides a consistent approach to security and data requirements for health applications and defines a workflow that an application can use to securely request access to data, and then receive and use that data.11

Above and beyond the value of FHIR for open Point of Service systems, we believe that with the recent release of the Bulk Data Access API12, FHIR can play a pivotal role in enabling open health data commons. The Bulk Data Access API, which by December 2022 has been incorporated in all major FHIR implementations, can handle requests on cohorts with multiple patients rather than just one patient at a time, in an easy to use formatted single file. Combined with the existing semantic interoperability that FHIR provides through its Resources (the data components which allow flexible composition and combination of a wide range of health data) we now have a means for supporting analytical workflows that require access to and processing of data in bulk. It is this new functionality of achieving semantic interoperability for bulk data through FHIR that we want to bring attention to as a means for building a health data commons.

FAIR data stations as the cornerstone for a data commons

Inspired by the work of van Reisen et al. (2021) in implementing the VODAN-Africa data infrastructure for monitoring COVID-19, we synthesize the concept of the hourglass model and the FHIR standard into “fair data stations” as the foundational element for creating a federative, networked health data commons. FAIR data13 are data which meet principles of findability, accessibility, interoperability, and reusability. This concept has recently gained traction, particularly in the context of research data. The GO FAIR Initiative lists 18 implementation networks that are currently underway.14

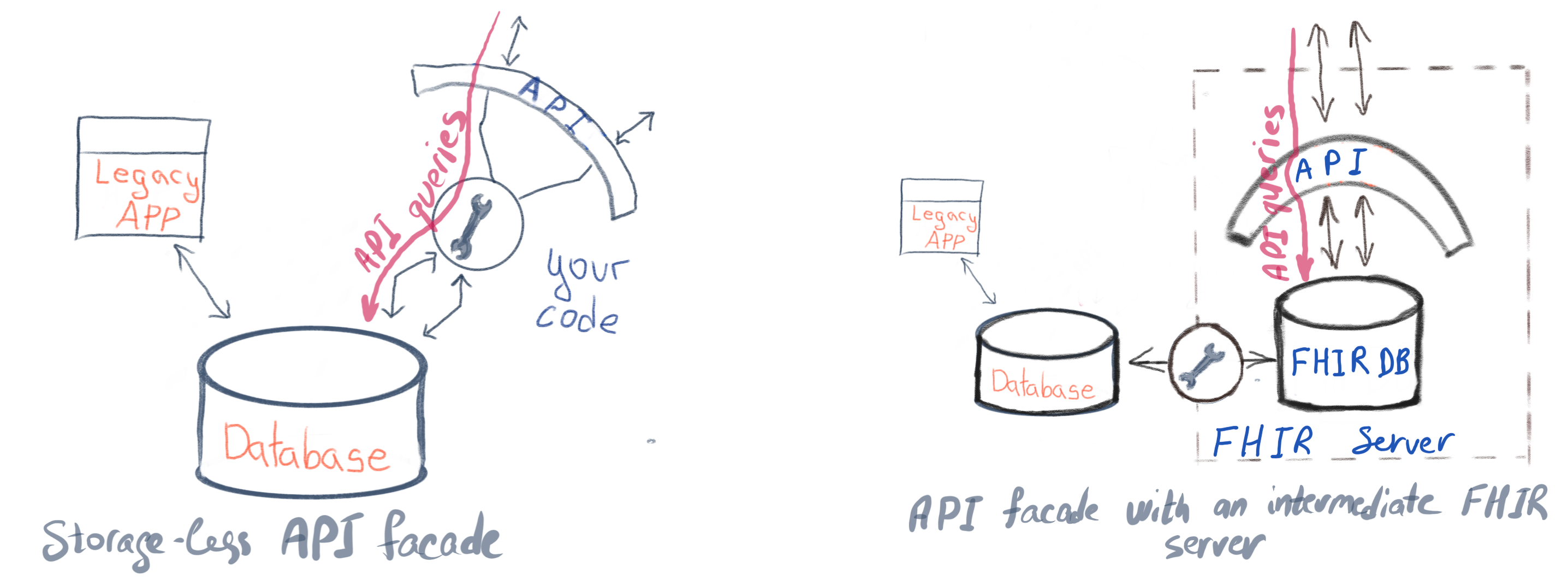

Gebreslassie et al. (2023) have analyzed that the FHIR standard can indeed be leveraged for the FAIRification process. They conclude that FHIR as a native solution through the protocols and specifications it supports, or with the community implementation guides, is a viable option for the FAIRfication process of health data. Furthermore, the widespread availibility of FHIR implementations also enables a transition strategy to enable data sharing of non-FHIR-based systems. The FHIR facade model provides a way to transition towards FHIR: rather than creating a FHIR repository to house the required data, the facade model data is fed directly from other repositories and converted to FHIR resources on demand. There are two ways to build a FHIR facade (figure 1.4):

- storage-less facade translates FHIR REST calls to queries to the underlying database or services of the original system. The internal information model is mapped to FHIR - find what FHIR resources and attributes represent data structures in your system. Such a facade passes all the calls to the original database.

- facade with intermediate FHIR server uses a generic FHIR Server for storing data that is going to be served over API. The same mapping of the internal information model to FHIR is performed but then synchronized data in the FHIR database with the data in the FHIR server that does the rest of the work.

Putting it all together

The design principles outlined above are integrated into the openHIE framework as follows:

- The Shared Health Record (SHR) component is the fair data station, the elemental building block of the data commons which is implemented using the FHIR Bulk API standard;

- The Interoperability Layer (IOL) provides the key functions for connecting a network of data stations, including

- Mediators as a storage-less facade for integrating non-FHIR legacy systems;

- Interlinking and routing services for search, metadata and other discovery services;

- Many of the Common Services will be implemented using the FHIR standard, where components such as Terminology Services and Facility Registries as specified in detail.

In the following chapter we introduce Momcare Tanzania, which is used as the testbed for this architecture.

This introduction is largely based on the Governing Health Futures 2030 report by the Lancet & Financial Times Commission.↩︎

We follow the definition of a data commons as described by work of Tarkowski and Zygmuntowski (2022).↩︎

https://www.who.int/news/item/03-07-2023-who-and-hl7-collaborate-to-support-adoption-of-open-interoperability-standards↩︎

https://www.ejohealth.com/, https://sovereignty.network/kickstarter.↩︎

https://hl7.org/fhir/uv/bulkdata/index.html, Mandl et al. (2020), Jones et al. (2021).↩︎

See GO FAIR website and specifically the page on implementation networks. Last accessed 15th August 2022.↩︎