Towards a health data commons in LMICs

Demonstrating fair sharing and reuse of health data in sub-Saharan Africa

Data commons as a catalyst for achieving UHC

The world lags significantly in its pursuit to reach the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) of universal health coverage (UHC).1 It is a widely held belief that digital technologies have an important role to play towards achieving this goal in low- and middle income countries (LMICs).2 Yet, no clear cut development paths are known as to how digital health can be used effectively and efficiently on a large scale in such low resource settings.3

We believe that digital technologies indeed have an important role to play in achieving UHC. More specifically, we posit that patient-centric data access and reuse is an essential element in systematically improving care delivery in LMICs. While data access and reuse has been put center stage in many studies, it is a complex and dynamic field of work. Academic research often fails to bridge the gap towards practice. Realizing a commons-based ecosystem of for data sharing is difficult, as it needs to overcome potentially conflicting interests of actors involved in the system. Ongoing rapid developments of digital technologies themselves make it difficult to access investment decisions in an already resource constrained context.

Despite the challenges, we want to demonstrate that patient-centric data access and reuse is feasible, today. We take the approach of “show, don’t tell”. Through implementing demonstrator projects that contribute towards the creation of a Health Data Commons (HDC), we show that health data sharing can be achieved in LMICs at acceptable cost and low technical risk. This document describes the learnings from the HDC project. Through these demonstrators we aim to initiate a paradigm shift as to how data sharing can be realized such that it can act as a catalyst towards achieving UHC.

Building on the openHIE framework

The HDC project takes the openHIE framework4 as a starting point, being the most generic and commonly used health information interoperability framework. This framework has by and large been adopted by sub-Saharan African countries5, including Nigeria6, Kenya7 and Tanzania.8

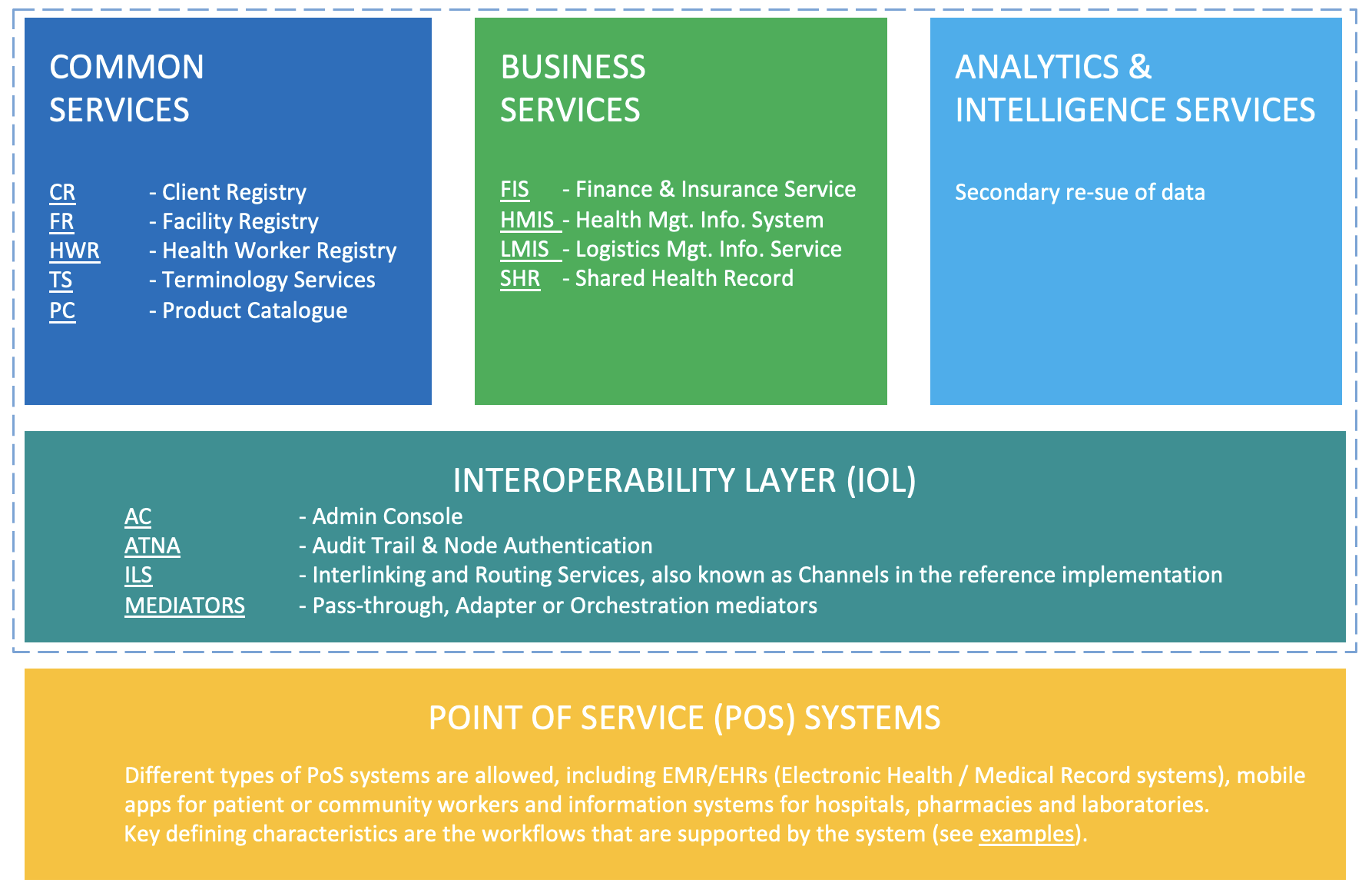

The HDC framework and its components are shown in figure 1. The bottom layer (yellow) comprises the point of service (PoS) systems, which includes the systems used by clinicians, health professionals, community health workers and the like. Examples of such systems are OpenMRS electronic medical records (EMR) system and the RapidSMS mHealth application, which are used to access and update a patient’s records, register activities and record healthcare transactions.

The second, middle layer (teal) constitutes the interoperability layer (IOL), which acts as a gateway for exchanging information between systems. Any type of information exchange, be it between two PoS systems, or between a PoS system and business services (explained below), is mediated through this interoperability layer. The interoperability layer provides functionality such as routing, translation services, auditing and authentication.

The top layer of framework comprises three distinct domains. Common Services (blue) include a variety of registry services that are designed to uniquely identify and track unique patients, facilities, healthcare products, and terminology that are used throughout the health data commons. Business Service (green) are designed to support the delivery of care within the health system. The District Health Information System version 2, for example, is a well-known and widely used Health Management Information System for collecting, analyzing, visualizing and sharing data through combining data from multiple PoS systems for a given geography or jurisdiction.9

The HDC framework explicitly adds a third domain in the top layer, which is not included in the OpenHIE specification, namely Analytics & Intelligence Services (light blue). The rationale for this addition is to facilitate secondary use of health data for academic research, real-world evidence studies etc. within the nascent concept of health data spaces.10 Note that the Kenyan Health Information Systems Interoperability Framework (KHISIF) has also explicitly included the analytics domain.

Shifting the paradigm for creating a health data commons

Over the last few years, the importance of interoperability of systems and reuse of data has become evident. One of the key challenges in establishing interoperability is the dilemma associated with economies of scope: start small, and run the risk of not achieving common standards. Start large, and get bogged down in talking rather than building a new standard infrastructure. Many actors in the healthcare domain believe that interoperability can only be achieved through top-down, centrally led design and implementation. At the same time, it is notoriously difficult to run such large scale programs effectively and efficiently. We believe this paradox is actually surmountable. Modern digital technologies and solution patterns for achieving interoperability are extensible and modular by design, and can be successfully implemented in a decentralized, federated fashion.

The hourglass model

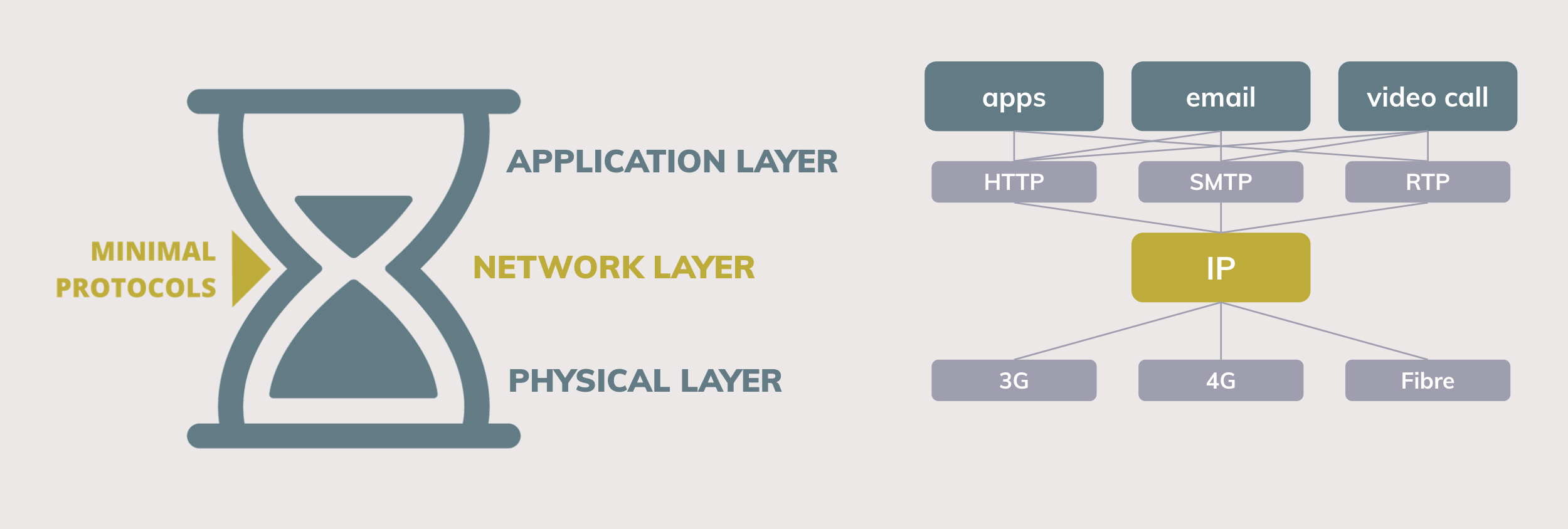

To illustrate this point, consider how the internet came to be since its inception. Beck (2019) argued that the success and ubiquitousness of the internet stems from its foundation on minimal, extensible standards. This so-called ‘hourglass model’ of the internet is shown in figure 2.

In essence, the hourglass model states that defining minimal standards (protocols) at the waist of the hourglass is crucial towards supporting a wide range of applications and supporting services at the top and bottom of the hourglass. For the internet, the IP protocol constitutes the center of the hourglass. Although the IP protocol is very limited in itself (it can only send and receive data packets), it is exactly because of its minimal standard that the IP protocol is able to support a great diversity of applications on top of it (web apps, email, videoconferencing) and allows implementation using a great diversity of supporting services below it (in this case, the many different types of physical networks). However, despite this flexibility and extensibility, the hourglass model strictly states that the components that lie above the central layer cannot directly access the services that lie below it.

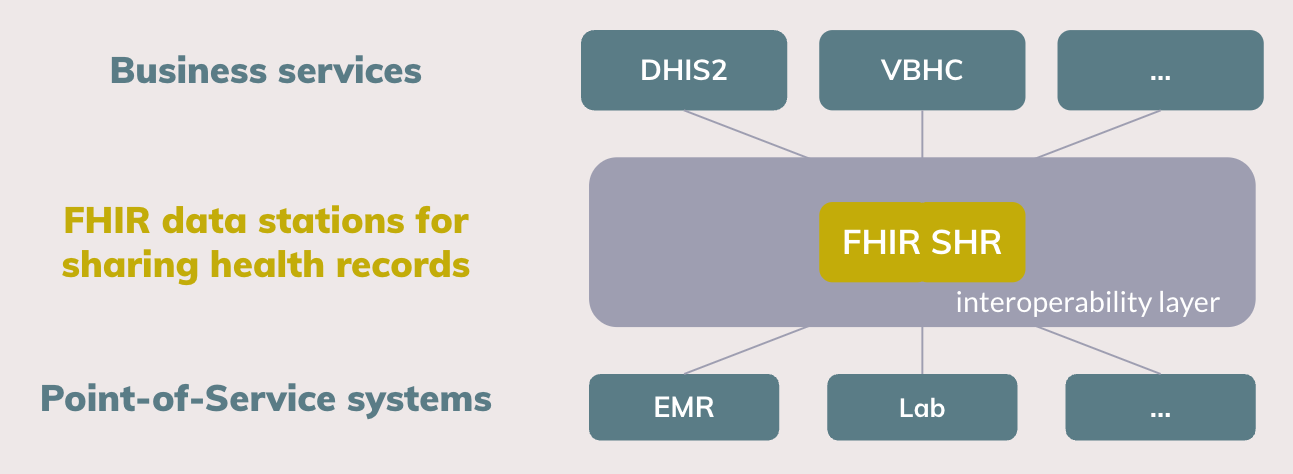

The hourglass model can be used as a foundational concept for a new paradigm on interoperability for health data, as is shown in figure 3. Essentially, we propose an integration of the design principles of OpenHIE, Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources (FHIR) and to make data Findable, Accessible, Interoperable and Reusable (FAIR).

FHIR as the de facto standard for health data exchange

FHIR has become the de facto standard for clinical information exchange in the healthcare sector, both for routine health data exchange11 and research settings12. The recently announced collaboration between HL7 International (the governing body of FHIR) and WHO exemplifies this trend.13 To date, however, the lion’s share of FHIR-related projects in LMICs focus on achieving openness and interoperability at the level of Point-of-Service systems. For example, the SMART on FHIR standard provides a consistent approach to security and data requirements for health applications and defines a workflow that an application can use to securely request access to data, and then receive and use that data.14

Beyond the value of FHIR for Point-of-Service systems, we propose to adopt FHIR as the elementary standard for realizing the Shared Health Record (SHR) component that is specified in the OpenHIE framework. We envisage FHIR SHR data stations at the center of the hourglass as the minimal standard for health data sharing. Higher lying business services can access health data as is persisted in the FHIR SHR, while lower lying Point-of-Service systems can interact with the FHIR SHR to read, write and combine the shared health record. As the FHIR standard is extensible in itself, that is, data sets can be composed out of the 100 elementary building blocks15, the implementation and roll-out of data stations can happen in a gradual manner. In the work presented here, we take the International Patient Summary (IPS) that consists of about 15 FHIR building blocks as the basis for the shared health record.16 As the use and reuse of health data grows, more data can be added to the FHIR SHR.

Alignment with FAIR principles

Our paradigm also aligns with the principles put forward by the GO FAIR community.17 For example, these principles have been applied in implementing the VODAN-Africa data infrastructure for monitoring COVID-19.18 Building on the experience from the VODAN Africa project, Gebreslassie et al. (2023) have analyzed whether the FHIR standard can indeed be leveraged for the FAIRification process. They conclude that FHIR as a native solution is a viable option through the protocols and specifications it supports, or with the community implementation guides.19

Implement HDC with modern technology

The OpenHIE community was formed a decade ago in 2013, and whilst the conceptual elements of the framework are still relevant and useful, a lot has changed in terms of available software tools and implementations. One of the key contributions of the HDC project is to implement demonstrators that comply to the openHIE guidelines using modern digital technologies. More specifically, we aim to leverage the following open source components:

- OpenHIM as core interoperability platform20: thanks to Jembi Health Systems and the open source community, the OpenHIM has matured over the last decade. The current version 8 is being used in various countries.21

- HAPI FHIR and Bulk FHIR API: HAPI FHIR is a complete implementation of the HL7 FHIR standard for healthcare interoperability, and is one the most commonly used open source implementation in LMICs.22 We demonstrate that this component can be used effectively to implement a Shared Patient Record that supports both primary use (exchange of single records between users) and secondary use (reuse of data of a whole population for analytical purposes). Furthermore, we particularly focus on using the bulk FHIR API as a means for supporting analytical workflows that require access to and processing of data in bulk.23

- Federated analytics and federated learning24: existing medical data is not fully exploited for secondary reuse primarily because it sits in data silos and privacy concerns restrict access to this data. However, without access to sufficient data, it is difficult to imagine how digital health can effectively contribute towards achieving UHC. Federated analytics and federated learning provides stepping stone towards addressing this issue. We envisage a health data commons where the FHIR SHR is accessible as a data station that participates in a federated analytics framework. Many mature open source components are available to this purpose.

We propose an integration of the design principles of OpenHIE, FHIR and FAIR for a new paradigm wherein FHIR data stations are the minimal standards for health data sharing. Beyond these design principles, however, it is not necessary to implement and deploy this ecosystem of FHIR data stations in a top-down, large-scale program. The internet was not built that way either. Instead, any health facility, county or consortium can start building and contributing towards implementing FHIR data stations that adhere to the FHIR standards and the principle of the hourglass model. Building the internet of health data, one data station at a time.

Demonstrators built for MomCare project

PharmAccess launched MomCare in Kenya (2017) and Tanzania (2019) with the objective to create transparency on the journeys of pregnant mothers. The program is built on three pillars: journey tracking, quality support and a mobile wallet. MomCare distinguishes two user groups: mothers are supported during their pregnancy through reminders and surveys, using SMS as the digital mode of engagement. Health workers are equipped with an Android-based application, in which visits, care activities and clinical observations are recorded. Reimbursements of the maternal clinic are based on the data captured with SMS and the app, thereby creating a conditional payment scheme, where providers are partially reimbursed up-front for a fixed bundle of activities, supplemented by bonus payments based on a predefined set of care activities.

In its original form, the MomCare program did not support interoperable data exchange. In Kenya, M-TIBA is the primary digital platform, on top of which a relatively lightweight custom app has been built as the engagement layer for the health workers. M-TIBA provides data access through its data warehouse platform for the MomCare program. However, this is not a standardized, general purpose API. In the case of Tanzania, a stand-alone custom app is used which does not provide an interface of any kind for interacting with the platform. Given these constraints, to date the MomCare program uses a custom-built data warehouse environment as its main data platform, on which data extractions, transformations and analysis are performed to generate the operational reports. Feedback reports for the health workers, in the form of operational dashboards, are made accessible through the app. Similar reports are provided to the back-office for the periodic reimbursement to the clinics.

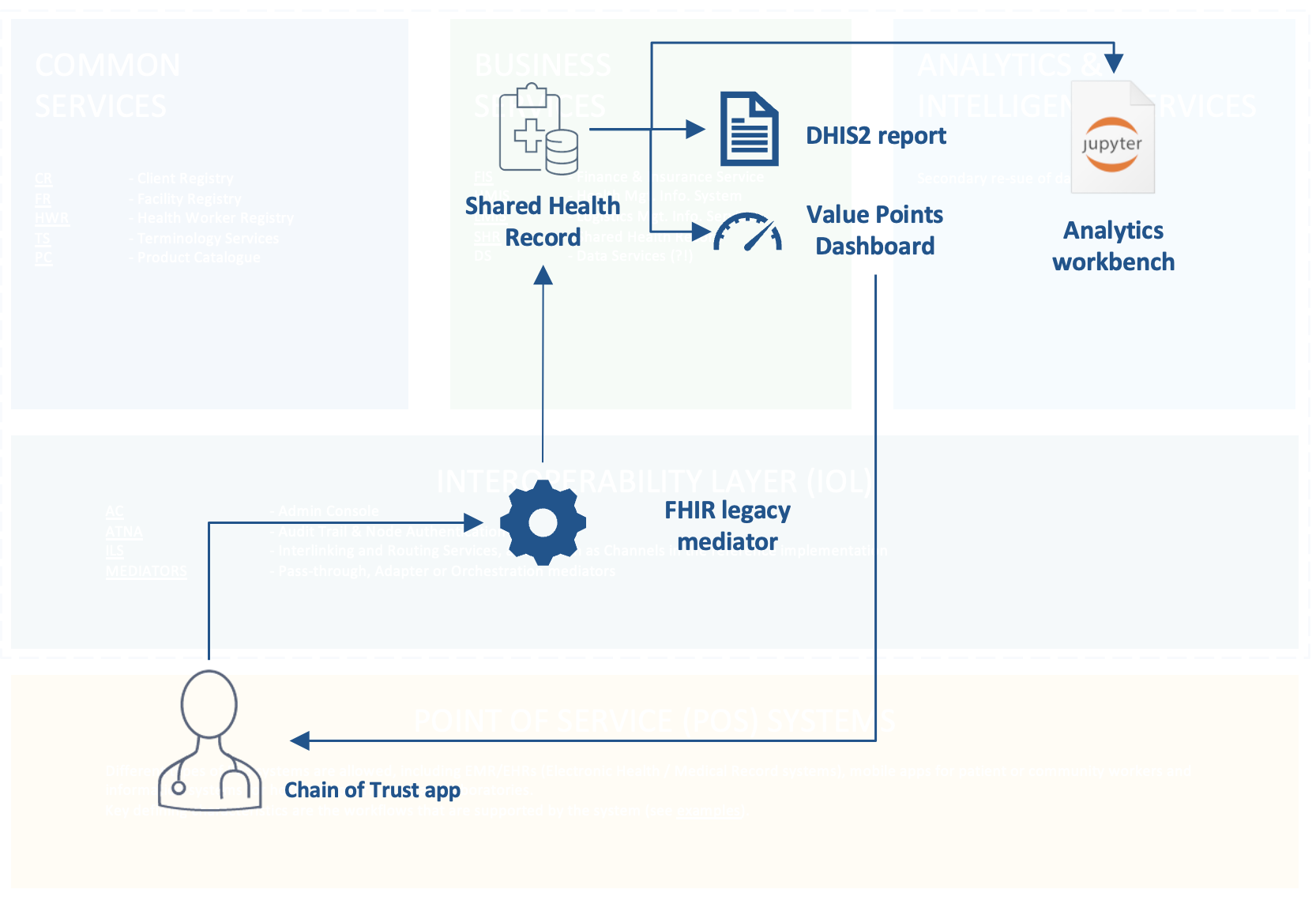

Within the this context of the MomCare program, we have built a number of demonstrators (components) to show how interoperability can be achieved using the HDC framework. figure 4 demonstrators illustrates how each of these components are positioned within the framework, where naming of components follows OpenHIE terminology.

- FHIR adapter mediator: data from the existing MomCare app is extracted and transformed into FHIR standard. The code is implemented in such a way that it can be readily deployed as OpenHIM mediator;25

- Shared Patient Record in Bulk FHIR format: data from all patients and participating health facilities in the MomCare program are persisted as Shared Patient Records using the Bulk FHIR data format. While the FHIR standard was originally designed as an interoperability standard for information exchange, we demonstrate its use for persistent data storage as means for realizing the Shared Health Record component. We demonstrate that the data can be stored and made accessible using standard cloud storage technologies to enable secondary reuse of bulk data through federated analytics;

- Business Services:

- Automated DHIS2 reporting: existing management reports can be reproduced and generated from the FHIR-transformed data, thereby reducing double entry and opening up possibilities to improve management reporting;

- Value-Points Dashboards: value-based care models and conditional payment schemes can be supported using the FHIR-transformed data. By using FHIR, data across different point of care service providers can be share and integrated, thus allowing the tracking of a full care journey from start to finish. Having visibility on the full patient journey is one of the key requirements for support value-based healthcare programs;

- Federated analytics workbench: we demonstrate the integration of the Shared Health Record with an federated analytics workbench. We add the global de facto standard of interactive, notebook-based computing of the Jupyter project26 to the openHIE framework.

Above mentioned demonstrators have been build using open source technologies and implemented using standard cloud technologies. Within the setting of the MomCare project, Azure was chosen as the cloud infrastructure on which the components have been deployed, but the components can be deployed on any cloud hosting provider.

Key findings

Required skills and development effort

The HDC project was initiated in Q3 2022, while the majority of the development work was conducted in December 2022 until July 2023. The core team consisted of 5 people with the profiles listed below, with two people taking up the software developer role, and one person for each of the other profiles.

- Perform all development work, both the back-end (data platform) and front-end (web app)

- Cross-platform and cross-language development skills are required (Java, Python, Javascript) as the open source components that were just vary greatly

- Also responsible for cloud engineering and managing the production environment (DevOps), in this case Azure

- Develop data processing pipelines, including transformation of source data into FHIR

- Perform data analysis and write standardized queries for the reports

- Develop interactive data visualization components, which were subsequently included in the dashboard app

- Design overall architectural framework of HDC

- Research and evaluate open source components to be used for specific use-cases

- Writing implementation guides and knowledge transfer to key stakeholders

- Define functional requirements of reports and dashboard via mock-ups

- Interface to key users in the field

| Role | Total mandays |

|---|---|

| Software developer | 90 |

| Data scientist | 30 |

| Solution lead | 10 |

| Digital architect | 30 |

| TOTAL | 160 |

| Use-case | Recurring development effort (mandays) |

|---|---|

| Implement FHIR mediator | 10 |

| Implement new dashboard on FHIR data | 10 - 20 |

| Deploy and configure FHIR SHR for a region | 20 |

table 1 shows the amount of time spent on the project. The development effort includes both the initial exploration and development of re-usable components, and the recurring effort required if these components are to be used for a new project. table 2 provides a rough indication what the recurring development effort would be for such new use-cases.

Lessons learned

Many of the lessons we learned whilst working on the MomCare Tanzania case confirm the truisms associated with doing data-related, digital development work. First, even with clear architectural guidelines in hand, there is a wealth of digital public goods and open source software to choose from. Choosing the best fit for a given use-case is often not evident, and in fact should be a continuous effort when scaling up the paradigm proposed here. We feel there is good work to be done in bridging the various worldwide communities, for example, the FHIR community, the OpenHIE community and the FAIR community.

Second, it was that standardisation really does add value and reduce the development overhead. Within a couple of months, we managed to deploy a FHIR data station using the HAPI FHIR server. That data station immediately gave us the possibility to query data uniformly and control access to personally identifiable information. We experienced the benefits of having standardized data for analysing data from different sources. We also found that applying data standards improves visibility on data quality.

Finally, we found that adopting best - or at least common - practices in our development work improved productivity and efficiency. For example, over the course of the project, three different team member contributed and improved on the FHIR translation scripts. Having detailed technical guidelines helped us to handover work efficiently, iterate quickly and reuse code.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the following open source digital public goods without which these demonstrators could not have been realized (alphabetical order):

- Apache Arrow and Apache Parquet are used as language independent data formats for the Shared Health Record component, allowing efficient storage and processing of small to very large datasets.

- duckdb is used as primary database system for performing analytics on Shared Health Record component.

- Project Jupyter as the de facto global standard for data analytics using interactive notebooks.

- svelte and svelte.kit frameworks for buidling offline-resilitient progressive web apps.

- Quarto publishing system. This document was authored using Quarto books.

- Vega-Altair and Vega-Lite data visualisation framework, used in creating dashboards and reports.

Kickbusch et al. (2021) and World Health Organization (2021)↩︎

Nigeria data exchange architecture for the national data repository↩︎

see for example the International Data Spaces Association↩︎

https://www.who.int/news/item/03-07-2023-who-and-hl7-collaborate-to-support-adoption-of-open-interoperability-standards↩︎

the so-called FHIR Resources↩︎

website FHIR Bulk Data Access, Mandl et al. (2020), Jones et al. (2021).↩︎